Why I Shut Off Comments for Millions of People

And why doing so was both unimaginably naive, and the only possible choice.

In September 2013 I was still finding my way as the new editor-in-chief of Popular Science magazine, and I’d just hired a very smart online director, Suzanne LaBarre, who came to me with an emergency. She’d just read some very scary research that suggested people couldn’t generally remember whether something they’d read online had been in an article, or inside the comments section.

Why was this so worrisome? Because, as she showed in example after example, our site was besieged by trolls writing pseudoscientific nonsense that contradicted the findings we worked so hard to report accurately. And in some cases those contradictions looked like they could cause real physical harm, as in an article about sexually transmitted diseases below which one commenter wrote a bunch of technical-sounding nonsense about the ineffectiveness of condoms.

“What do you think we should do?” I asked her.

“I think we should turn off the comments,” she answered.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, as the heads of several of the largest social media platforms back away from their rules about what can and can’t be posted or amplified online. Taylor Lorenz has been following this issue for a long time, writing in a recent issue of User Mag…

After gaslighting content creators for years about their moderation practices, Meta has finally admitted that the company has gone too far when it comes to content moderation. Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, told reporters on a press call on Monday that the platform’s moderation “error rates are still too high” and that the company will attempt to “improve the precision and accuracy with which we act on our rules….”

Clegg’s confession comes after years of aggressive moderation efforts and down-ranking creators who post too frequently about news, politics, or social justice issues. Instagram meme pages and news accounts in particular have suffered as Meta cracked down on “disinformation,” often failing to distinguish obvious humor from legitimate false information.

Lorenz works hard to lift up parts of online culture that traditional assignment desks consider unserious, and I understand her take. But I read Clegg’s words on moderation not with a concern for creators, but with a concern for all of us. Why? Because of the decision we wound up making back in 2013, one that in retrospect was deeply naive, but one I’d make again in a second. Frankly, it was the only defensible decision. On Tuesday September 24th, I took Suzanne’s suggestion and we shut off all comments on the site. Here’s how she explained it to our readers:

A politically motivated, decades-long war on expertise has eroded the popular consensus on a wide variety of scientifically validated topics. Everything, from evolution to the origins of climate change, is mistakenly up for grabs again. Scientific certainty is just another thing for two people to “debate” on television. And because comments sections tend to be a grotesque reflection of the media culture surrounding them, the cynical work of undermining bedrock scientific doctrine is now being done beneath our own stories, within a website devoted to championing science.

We made the decision together in under 15 minutes, and emerged confident that we’d made the right choice. But I underestimated how controversial it would be. That afternoon I was hauled into my boss’s office to explain why I’d cost the site so much traffic and engagement, and by Thursday I was defending the decision publicly because, although I didn’t know it at the time, we were the first national publication to make this choice. Here’s how I summarized our logic to NPR’s Robert Siegel on All Things Considered:

SIEGEL: Why are you ending comments?

WARD: We had three deciding factors that it came down to. One is the rise of trolls, which is a pretty well-understood term these days - basically, people who come into a comment section of a website to be abusive or unpleasant. Second, we had bumped into on our own site, and then had seen it sort of confirmed in other places - and seen, also, studies about this - we discovered that troll behavior - that being unpleasant, being uncivil, sort being really fractious in a debate - can cause readers to actually misunderstand things that are scientifically validated.

And third, we decided that it was a matter of resources. There is a way - there are many ways to patrol the comments on one's own site; but if we have a limited number of resources - and everybody does - I'd rather pour that into our primary mission, which is great journalism; putting out the best science journalism we can, rather than just trying to patrol our comments for all time.

Here’s how I tried to explain it to our readers in a video we posted that week…

My conviction at the time was that we couldn’t responsibly publish anything under our name that we couldn’t take editorial responsibility for, and that includes active efforts to misinform our readers. I still believe that to be true. But I also assumed at the time that anyone running any site would feel the same way, and thus I concluded that we needed to push our commenters to sites that had the resources to patrol and moderate responsibly, because surely they could and would do what we couldn’t. And what sites were those? (Oh man, I was so naive. Wait for it.) Twitter and Facebook.

Maria Konnikova of The New Yorker seized on our decision to argue that the best place for reasonable commentary was inside an institution that imposed cultural norms on its readers, and that the wild, open countryside of social media had no cultural norms, and would thus lead to even more credible-sounding-but-utterly-wackadoo commentary. And she was right. Within a few years, after interviewing dozens of social media executives, I even came to understand that many if not most of them were outright hostile to the notion of any curation at all. Their libertarian logic seemed to be that the market would decide whether a paid staff of journalists like mine or a rabid pack of anonymous commenters were more worthy of attention and credibility. They felt they had should play no role in it other than offering the means to post.

In fact, the legal framework that allows modern social media to exist depends on the notion that they don’t have any responsibility for what’s posted on the platform. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act allows the operators of social media platforms to avoid culpability for what third parties post on their platforms. Legal scholars refer to this as “safe harbor.” Facebook, Instagram, TikTok and the rest are not legally considered the “publisher” of what we post on their platform, and thus have more or less no responsibility for it. This makes their business possible, because while a magazine like Popular Science has legal responsibility for what it publishes, and can be the subject of a business-ending lawsuit if they run afoul of the wrong party, people can say more or less whatever they like on social media, and the companies that make that commentary possible don’t have to patrol it for accuracy.

But we had no choice. Keeping comments up on our site was a guarantee of misinformation, because with an annual editorial budget as small as ours, one shrinking each quarter, we couldn’t afford the personnel required to patrol even one day’s articles for misleading comments, much less those attached to articles going back years that kept finding traction in Google search results. Social media companies, which were clearly replacing the role of magazines like mine, were the only ones with the money necessary to fight what I considered a holy fight against deception. And until recently, the heads of those companies did make some attempt to moderate dangerous misinformation. The pandemic saw a surge in exactly the kind of terrible stuff we were attempting to fight at Popular Science, and Facebook, Twitter and others adopted a policy that spiked certain categories of misleading posts about health, infection, and vaccines. At the time, I was encouraged that they chose to do so. These are the platforms whose business model outgunned small magazines like mine, and created such an uphill economic battle for traditional journalism that in my view it may not survive. Clearly they had to take some responsibility for the result.

But now, most of those companies are actively backing away from content moderation. In August Mark Zuckerberg apologized to House Republicans for censoring misinformation about COVID-19. And in September, in front of a jubilant crowd in San Francisco for a live taping of the Acquired podcast, he said that taking on too much responsibility for what happened on his platform was a top regret in 20 years running the place.

One of the things that I look back on [and] regret is, we accepted other people's view of some of the things that they were asserting that we were doing wrong or were responsible for. I don't actually think we were.

Elsewhere in the episode he told his interviewers that he wouldn’t be making the mistake of over-apologizing in future.

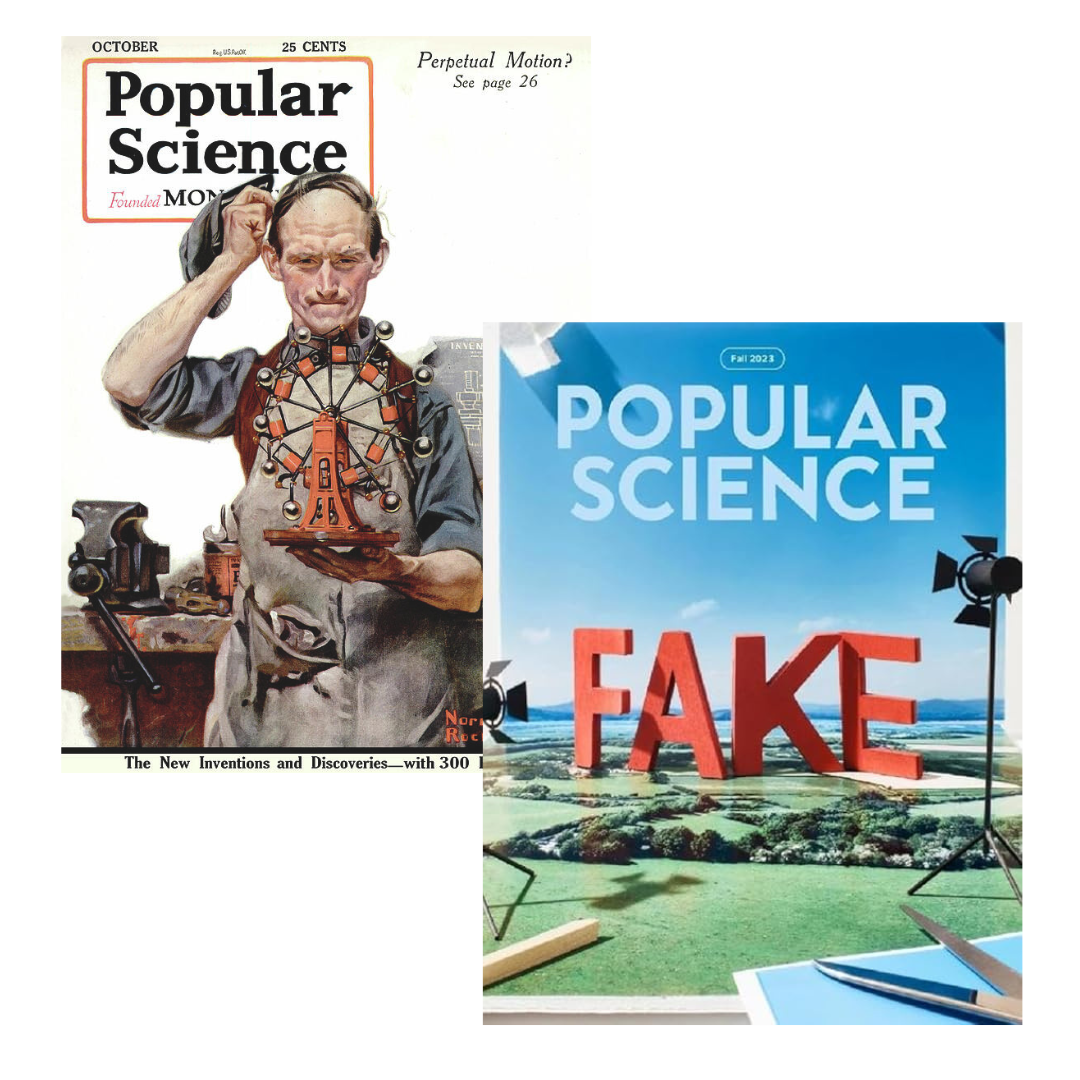

Meanwhile, the news business is collapsing, not least because social media companies, which made themselves central to how people read the news, are now turning away from carrying news content at all. Facebook and Twitter referrals were our top source of traffic during my time at Popular Science. One or two big hits on those platforms could single-handedly account for a month’s worth of traffic. But since January 2023, referral traffic from Facebook to the top news publishers has fallen by 40 percent. How anyone is surviving is beyond me. We certainly didn’t. After nearly two centuries in business, the last print issue of Popular Science was published in April 2021. The magazine's last online issue, which carried the headline "Fake," was published in September 2023.

I’m writing this to you as someone who has been through several categories of media as a professional journalist, and who is now experimenting with the last version of it that holds any promise of pay, a sort of public-patronage system in which only a handful of people can hope to break through. The platforms whose business model led us here don’t seem interested in replacing the civic function of journalism, and the market value of objective reporting has collapsed. A November report from the Pew Research Center that looked at news influencers with more than 100,000 followers found that

About one-in-five Americans – including a much higher share of adults under 30 (37%) – say they regularly get news from influencers on social media.

News influencers are most likely to be found on the social media site X, where 85% have a presence. But many also are on other social media sites, such as Instagram (where 50% have an account) and YouTube (44%).

Slightly more news influencers explicitly identify as Republican, conservative or pro-Donald Trump (27% of news influencers) than Democratic, liberal or pro-Kamala Harris (21%).

A clear majority of news influencers are men (63%).

Most (77%) have no affiliation or background with a news organization.

(That last bullet point is part of why I launched this newsletter. And if they have no training, I hope they’ll at least publish and observe a set of ethical standards.)

Social media platforms have launched side hustles and occasional full-time careers for millions of people who identify as creators, and I think reporting on that industry is a vital journalistic task. (Substack writers like Lorenz, Casey Lewis and Maria Santa Poggi and Sara Radin of trendfriends are worth following.) But just because social media companies have convinced so many people to bet their livelihoods on being creators, and wound up with a morass so complicated that even they, with their billions, can’t effectively patrol it, doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t be responsible for doing so. In my most frustrated moments my thinking becomes very simple, and very binary. If you can’t drive the car safely, you shouldn’t be allowed behind the wheel. If you create a machine so powerful you can’t keep society safe from it, shouldn’t you have to turn it off?

At the very least it seems to me that the least that social media companies can do, after killing off the fourth estate, is to try to keep what replaces it from actively misleading us. But that view is falling out of fashion, and in a nation that invented the attention economy, a nation that gives the resulting industry broad exemptions from liability, and a nation without any federal data privacy laws, fashion is all we have left.

I'm curious if the original study your colleague mentioned, the one that suggested that people couldn't remember if what they read was in the comments section or in the article, took into account whether or not the comments people remembered were actually factual. For instance, for the sake of argument lets assume 10% of the comments in the comments section are actually factual. Do people remember the comments that were factual or do people remember the ones that are just trolls?

Isn't part of the reason for the pendulum-swing of social media company policies on COVID that they over-moderated in some cases, incorrectly suppressing legitimate discussion of disputed issues as misinformation?

I'm thinking here particularly of the lab leak hypothesis, which IIRC Facebook at least suppressed posts about for some time in 2020-21. Eventually they turned around on it because the evidence that that hypothesis _might_ be true (and "might" is still the right word!) became too strong, and because principled, knowledgeable people like Zeynep Tufekci called them out on it. But the damage was done, in the sense that they've handed a talking point now to all the people who might say "what ELSE doesn't Big Media want you to know, hmmm?" or the like.