TikTok Overturned an Election in Europe, Officials Say. But the Ban Here Won't Protect Americans.

The platform was implicated in a Romanian court's shocking decision this week. But the US shouldn't ban TikTok without regulating the nation-like power of the rest of social media.

Disclaimer: Before I get going here, you should know that TikTok is my primary social media platform as a consumer and as a creator, and it’s the only one on which I’ve found any real popularity. Casually posting to that platform over the last few years has given me at last count about 87,000 followers, which means that a federal ban would cost me my single greatest source of exposure. (I haven’t yet been paid by TikTok, but as I understand it my posts would earn me a one-time payment of about $300, so in my view a ban wouldn’t cost me any real income.) All of this is to say that while I’ve been covering this subject for years, it’s not an entirely abstract one for me, and you should know that going into today’s post.

On Friday a panel of federal judges upheld the law that would ban TikTok in the U.S. in January unless it finds an American buyer. “The First Amendment exists to protect free speech in the United States,” they wrote. But “here the Government acted solely to protect that freedom from a foreign adversary nation and to limit that adversary’s ability to gather data on people in the United States.”

ByteDance, the Chinese owner of TikTok, looks pretty screwed. TikTok had petitioned to overturn the law, signed by President Biden in April. As of today, that petition is denied, and only the Supreme Court can say different, if they’re even willing to hear the case. Trump’s people have spoken of somehow rescuing the app, but don’t seem to have any clear legal means of doing so. At an estimated value of $200 billion, this isn’t an easy purchase, and those few companies that can afford it would likely wash onto the rocks of antitrust regulation. And Chinese officials, spoiling TikTok’s efforts to portray itself as independent of Beijing and of no direct geopolitical value to the CCP, have said (in typically vague terms) that they wouldn’t want the sale to go forward. The ban is due to take effect on January 19th.

TikTok is used by nearly one half of Americans, making it what I would argue is the most successful cultural and technological import in American history. And as I’ve discussed many times (you can hear me go on an on about the TikTok ban with Chris Hayes on his show), TikTok’s business model is no different than that of any other social media company. Attention, filtration, repeat. It just happens to have invented a system in which even those with no celebrity pull and only a few followers can win viral popularity, casino style, with billions of people around the world.

TikTok’s business model is no different than that of any other social media company. Attention, filtration, repeat. It just happens to have invented a system in which even those with no celebrity pull and only a few followers can win viral popularity, casino style, with billions of people around the world.

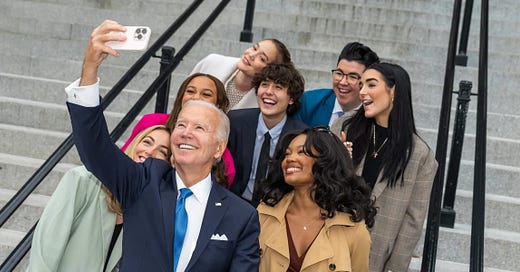

In this way, it has an ironic anyone-can-make-it veneer of democratic possibility to it, and TikTok has made masterful use of the everyday people who found fame on their platform, trotting them out in public appearances to speak out against the law. (You can watch the company’s CEO Shou Chew, speak directly to those users here.) It’s also the preferred medium of young voters, which has put everyone involved in the ban in an impossible position. Even as he prepared to sign the law that may seal their accounts’ fate next month, President Biden actively courted TikTok creators in public photo ops in Washington. It’s a weird moment.

But the machinery of TikTok isn’t an open democracy — it’s a proprietary system, like any other company’s, and its gears are hidden from the public.

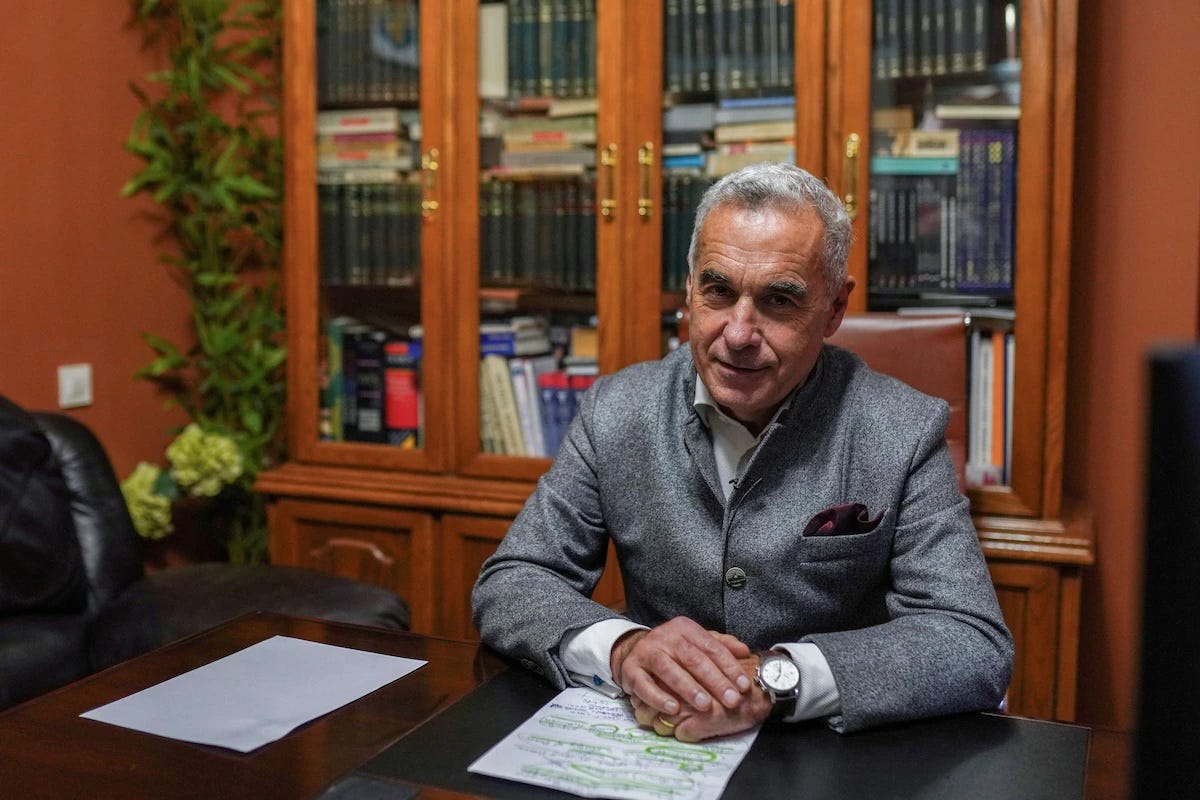

On the same day that federal judges here brought a US ban closer to reality, Romania’s highest court canceled that country’s presidential election after intelligence services there determined that “Russian hybrid actions” through TikTok had given a previously unknown candidate, Calin Georgescu, first place in the contest. The Chinese platform is specifically and prominently mentioned. Georgescu came from nowhere to win more than 22 percent of the vote. His pro-Russian positions included a vow to block vital grain shipments to Ukraine.

“The Government will set a new date for the election of the President of Romania,” the court wrote in a binding decision. Euronews summarized the findings of newly declassifed intelligence documents, which called Georgescu’s win “not a natural outcome,” this way:

According to the Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI), a previously hidden network, mainly operating on TikTok, which had been largely dormant since its creation in 2016, became very active in the two weeks before the first round of the elections. The network's operators, recruited and coordinated through a channel on the messaging platform Telegram, used methods typical of a state actor's "mode of operation."

The SRI also reported that nearly one million euros were spent in the campaign by an individual supporting Georgescu's candidacy, with up to €950 paid for a repost. TikTok itself admitted to receiving €362,500 from this person last week, the documents showed.

The declassification sent shockwaves through Romania and beyond, stoking fears the Eastern European country had fallen victim to foreign interference.

Lawmakers in the US haven’t offered any specific domestic examples of interference or propaganda affecting TikTok users here, but Romania is now the most direct evidence yet of the potential for both. Until now the most logical case for banning TikTok in the U.S. was a question of trade balance. China doesn’t allow American social media companies to do business there, but we allow theirs to do business here. We wouldn’t allow this with steel, the logic goes, so we shouldn’t allow it with digital products. But the law is written to protect Americans from spying and propaganda, and that’s what seems to have carried it past this panel of judges.

Here’s how I look at that threat, whether it’s unique to TikTok, and what this potential ban makes clear about the broader threat being ignored.

TikTok, domestically operated as an American company, is of particular concern because of its ownership, through ByteDance, by a country actively hostile to the United States. (Chinese law mandates that companies there must closely cooperate with intelligence agencies.) Last month Josh Rogin revealed in the Washington Post that Chinese hackers connected to Beijing are currently “inside the private wiretapping and surveillance system that American telecom companies built for the exclusive use of U.S. federal law enforcement agencies.”

China clearly wants as much information about us as it can possibly achieve, just as we would want as much as we can get about people there, and a social media platform on which one-half of Americans volunteer their thoughts and rabidly consume content is an incredible strategic asset. A Cold War spymaster who built a surveillance device so pleasurable that people around the world happily used it an average of an hour and a half every day would get a statue the size of a rocket.

A Cold War spymaster who built a surveillance device so pleasurable that people around the world happily used it an average of an hour and a half every day would get a statue the size of a rocket.

The espionage threat is real. But here’s the thing: we don’t protect our citizens against being spied on at all at the moment, as long as it’s Americans doing the spying. The United States has effectively zero federal data privacy protections in place. Whatever you buy, write, or record and post online goes into a vast, unregulated surveillance economy that has helped to make the largest tech companies into nation-sized actors. And I’d argue that letting a handful of unelected billionaires control the fundamental circuitry of interpersonal communication in the United States also constitutes a nation-sized threat to the average American.

The laws we currently have in place to make sure American companies don’t act against the interests of the United States date from a time when companies earned only hundreds of millions in revenue, and sold primarily to Americans. Today they earn hundreds of billions, and have interests and relationships around the world. (I’ve sat onstage with executives from the biggest American tech companies and struggled to get them to even say the word “China,” much less publicly criticize its policies or government.)

It’s too much to say that social media companies are nation-states that pose a national security threat to the United States. But I do think that the apparatus we have in place to account for that sort of threat doesn’t account for the surveillance giants that currently roam the earth. When the FDR administration created the first export controls in 1940, they were not thinking of Elon Musk, who has risen to a supra-national position of influence atop one company that directly constitutes the news diet of 1 in 5 American voters while another of his companies operates a fleet of satellites so large and so vital to military communications that they’re often the only way to communicate in a war zone, and can actively change the outcome of a conflict.

It’s too much to say that social media companies are nation-states that pose a national security threat to the United States. But I do think that the apparatus we have in place to account for that sort of threat doesn’t account for the surveillance giants that currently roam the earth.

And even if American social media companies don’t fit the court’s idea of a foreign adversary, we know that they offer a useful opportunity for foreign adversaries to make inroads in the United States. Here’s how Tim Wu of Columbia University described it to me for a 2019 article about the dangers of giving away our data:

There’s an incredible concentration of power there. So much data, so much influence, makes them a target for something like Russian hackers. To influence an election, you used to have to hack hundreds of newspapers. Now there’s a single point of failure for democracy.

Democracy did fail, and right at that single point, according to Romanian intelligence officials. Now the perceived legitimacy of the government is at stake. Romania’s Prime Minister-elect applauded the court’s decision and said “the authorities' investigations must show who is to blame.”

Several candidates there are trying to undercut the decision as quickly as possible. Elena Lasconi, who placed second and would have squared off with Georgescu on Sunday, said in a video that “the Romanian state has trampled on Democracy.” She posted it on Facebook.