Those Who Remember Dictatorship

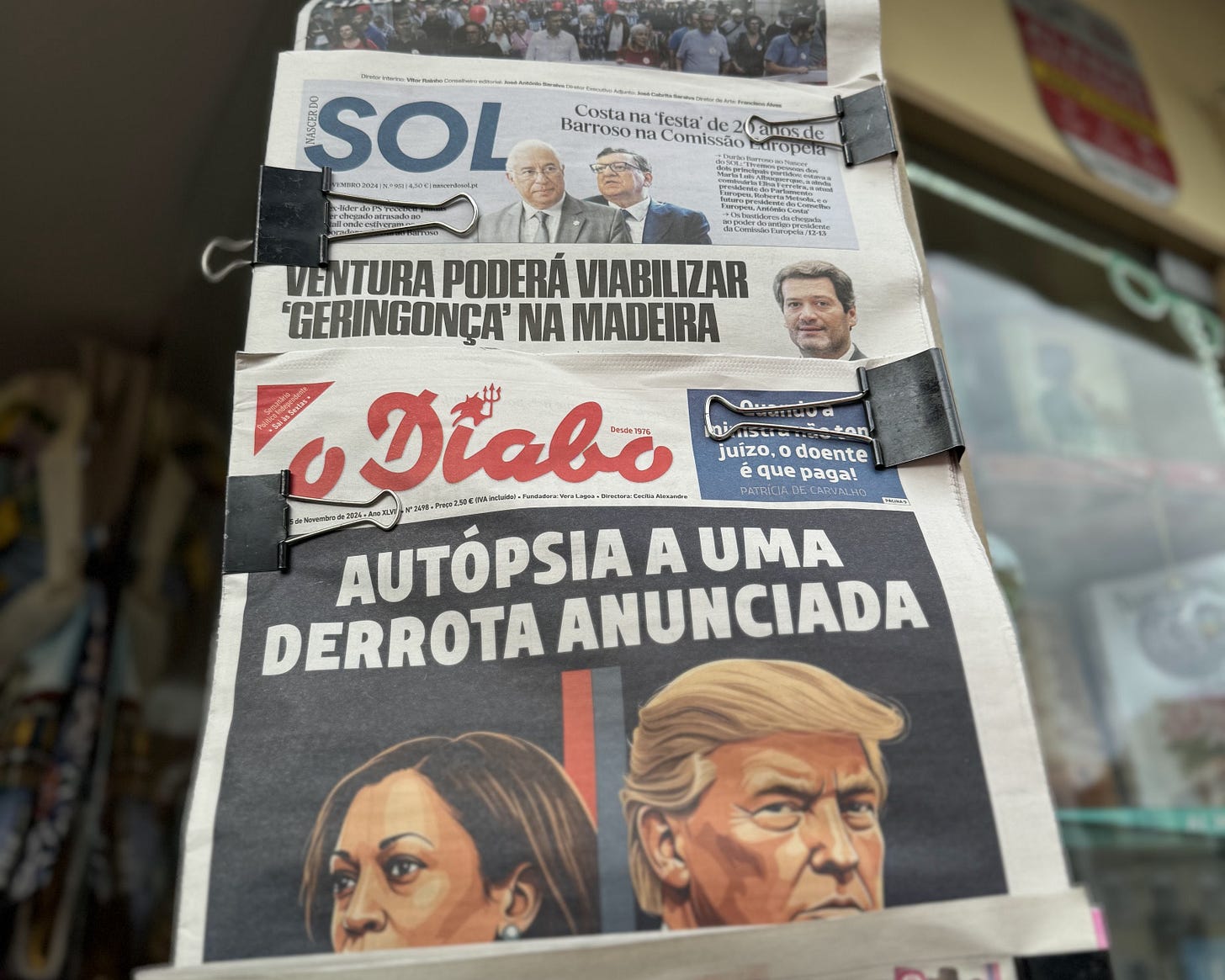

All over the world, people walking the streets today know what it is to watch basic freedoms slip away. This week they managed to save democracy in South Korea.

First: some news. Then: a travel story.

On Tuesday night President Yoon Suk Seol imposed martial law on South Korea. The reasons he gave (that opposition party members are North Korean sympathizers) made little sense, and the declaration followed months of frustration with budget battles and corruption investigations into the people around him, including his wife. Whatever his reasons, he created chaos for six hours. Soldiers occupied parliament, helicopters circled above, and lawmakers had to scale walls in order to get inside and cast their vote nullifying his order. On Wednesday several opposition parties moved to impeach him, as demonstrators chanted in the streets, some driving great distances from their homes to make their voice heard. The New York Times reports that President Yoon is not just politically isolated, but has remained out of sight since his declaration Tuesday night.

The events of this week are especially traumatizing for a generation of Koreans who lived under the military dictatorship of Park Chung Hee, a Korean army officer who won the presidency in 1963, ushered in sweeping economic improvements and forged deep ties with the United States, and then, in 1972, imposed a military dictatorship that crushed political dissent and free expression. His head of intelligence shot and killed him at a 1979 dinner in his honor, throwing the nation into political chaos, and democracy didn’t return to Korea until 1987.

As one protester in her 60s told The Washington Post this week, “we’ve lost far too many people because of past martial laws.” She said she rushed to the National Assembly as soon as she learned about Yoon’s declaration. “I had to come out here to prevent history from repeating itself.”

There are millions of people around the world like her who have either survived dictatorship, or are currently living under it. They know better than the rest of us how fragile democracy is, and how hard it is to resuscitate once its pulse fades.

I was lucky enough to chaperone my Mom on a weeklong trip to Europe recently. She was there to see elderly friends in Switzerland for what will likely be the last time in her life, and wanted my company, and like anyone as old as these lovely people they were only really able to host us for a handful of days. But the journey was going to blow up our circadian rhythm and cost us more than 11 hours of flying time, not to mention thousands of dollars, and so we decided to make one other stop before flying home to California, and we chose Lisbon, Portugal.

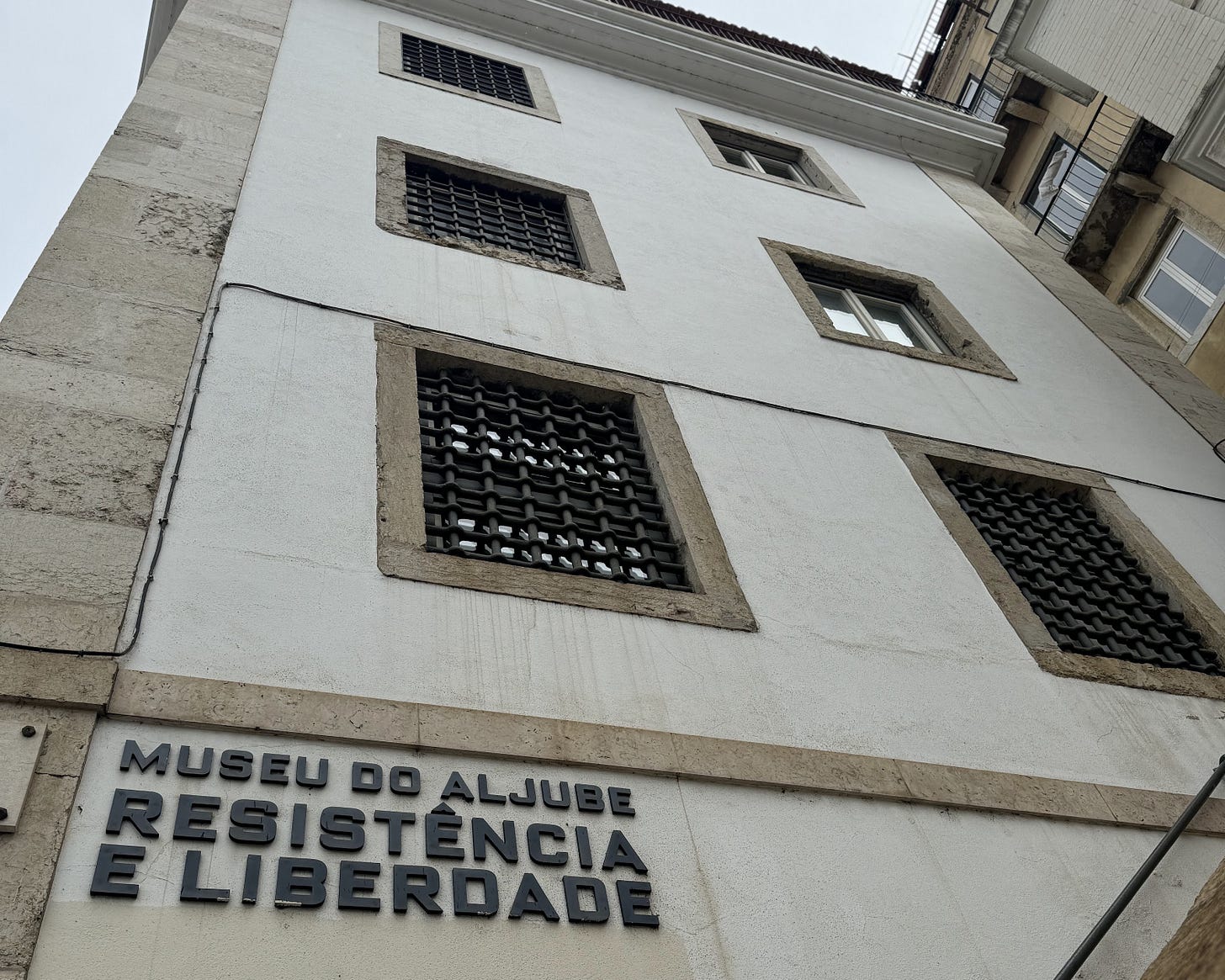

Neither of us had been there before, and on our first day we wandered around the city in a naive, unplanned way. We marched up one maniacal staircase after another, gawked at the views from a hilltop castle, paused at cafes for pasteles and an espresso. And then, as a light rain began to fall, we looked up and saw we were in front of a very ominous-looking building whose sign told us it was the Museu do Aljube, above the words "Resistência e Liberdade."

My Mom was the better traveler that day, and wanted to go inside. I hesitated — A museum? Already? And what was with all the bars on the windows? — but followed her in, and within five minutes my perspective on everything from Portugal to Trump to social media had been violently rearranged like a shaken jar of coins.

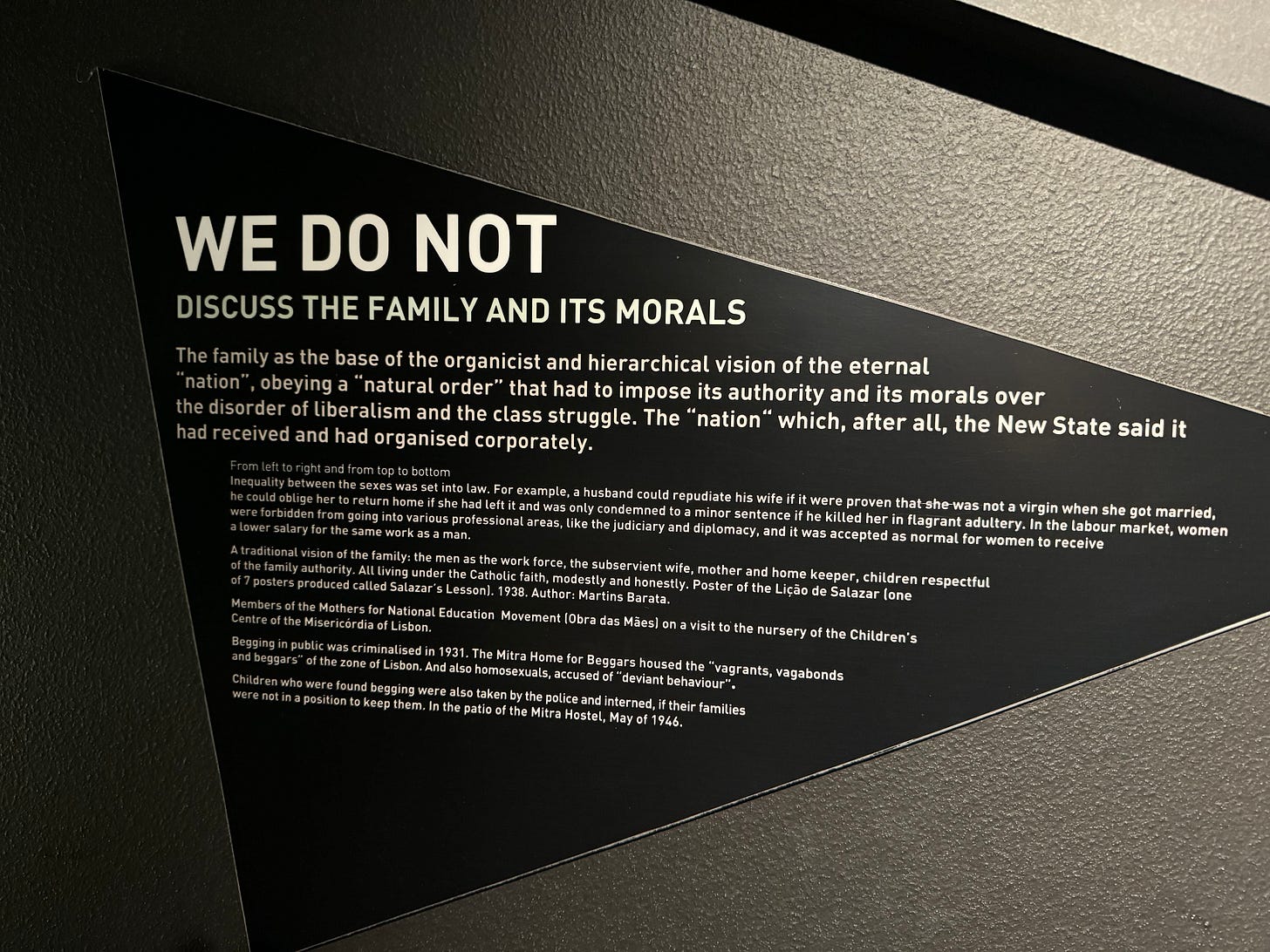

It will undoubtedly be the case that many of you already know your modern Portuguese history, so forgive me if that's the case, but I've described this to dozens of people in my social and professional circles in the last weeks, and they're as shocked as I was to learn about the horrors Portugal experienced in the 20th century. For roughly four decades, until 1974, the nation was under authoritarian rule imposed by the dictator António de Oliveira Salazar. His regime, born out of economic dissatisfaction, created a terrifying surveillance state, imposed broad laws about personal morality, enshrined inequality for women, and imprisoned and killed thousands of Portuguese for crimes as small as just speaking out against him. I'm embarrassed to admit that before standing inside that museum I knew nothing about any of it.

Aljube had already been a prison for centuries, under various Christian and Muslim rulers, when Salazar came to power and made it the first, horrible stop in a labyrinthine system of prison facilities and concentration camps. The museum today gives uninformed visitors like me a crash course in a largely overlooked episode of modern totalitarianism, one that anyone over the age of 60 directly experienced in Portugal.

Salazar was a distinguished professor of economics when a rising military dictatorship in 1926 offered him the role first of finance minister, and then, in 1932, of Prime Minister. He had a sinister talent for the job, establishing what he called an estado novo (new state) that he told Portugal would transform it into a modern economy. At that time, a tiny fraction of the population enjoyed modern comforts like electricity, sewer systems, and ready access to a physician. So the nation was hungry for improvement. But his goals weren't just economic.

In a speech given shortly after he assumed the top office, he spoke about the "unquestionable truths" of Portuguese life, telling his audience that true Portuguese do not speak about God, or the role of women in the home, or Portugal's place in the world. He was dictating from above that these were settled matters, that a "natural order" had to be imposed on the chaos of liberalism, and he was forbidding his country from raising any questions about them. It was the beginning of decades of stifling repression.

The museum features a crushing array of first-hand accounts of life under Salazar, from the imposition of laws that enshrined lower pay for women and that forbade them from entering professions like the law or diplomacy, to the purging of everyone from journalists to scientists for lack of political loyalty. One installation shows a special typewriter case designed to muffle the noise of the keystrokes — because the dangerous sound of an unregistered typewriter might invite the scrutiny of a bufo (informant) or member of the pide (secret police).

As the dictatorship grew more energetic and openly cruel, Aljube became a place of not just imprisonment, but torture. Women were often shown their babies held in the arms of a guard to motivate them to give up other revolutionaries. Sleeplessness, beatings, and sexual assault led to trauma, lasting injury, and often death. And for many, Aljube was a gateway to horrible fates in faraway Portuguese colonies like Angola, where the regime maintained outright concentration camps.

And even as the rest of the Western world saw gradual, steady shifts toward democracy and freedom, Portugal was denied again and again. The end of World War II and the victory of the Allied powers caused Portuguese to hope Salazar might be deposed, but that didn't happen. The widely supported candidacy of an opposition member, Humberto Delgado, earned him only 25% of the vote when he ran alone against Salazar's regime in 1958, and after years in exile he and his secretary were ambushed and murdered on the Spanish Border in 1965. The 1961 hijacking of the passenger ship Santa Maria by 25 rebels in an effort to bring international attention to Portugal's plight went nowhere after US naval forces surrounded the boat off Brazil and negotiated surrender and asylum for the attackers.

In the end it was Salazar's irrational attachment to his colonies in Africa, the Caribbean, and Asia that did his regime in. While England, France, Italy, and Belgium were giving up their colonies, Portugal formed an alliance with South Africa and Southern Rhodesia to hold fast, and wound up overspending its money and its political capital on the effort. Rebels in Angola and elsewhere began attacking the regime's outposts, and the political and financial costs became increasingly unbearable.

Salazar never lost his grip on power, however — at least not that he knew of. In fact, after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage after a fall and emerging from a one-month coma in 1968, his regime did not tell him that his office had been passed to a successor, and until his death in 1970 he was convinced he was still in charge. It wasn't until a small group of military officers staged a coup on April 25, 1974 — two months before I was born — that the road to democracy finally opened.

After several hours at Aljube, I reeled out of there, horrified at what the country had been through, shocked that after years of reading history this was all news to me, and speculating wildly about what might have been.

For one thing, my Mom and I discussed just how amazing it was that the various rebel forces arrayed against the estado novo were able to in any way coordinate their actions through printed materials and passed letters. How could a faction in faraway Angola stay in touch with a faction in Portugal?

And so we naturally talked about the Internet. Wouldn't it have hastened Salazar's fall? Surely it would have made resistance easier to coordinate. But I was — and remain — uneasy about this tidy answer.

The original, academic Internet — the era of email and bloggers and message boards and RSS — seems like the sort of thing that was made for revolution. A VPN and a daily burst of communication could have put faraway comrades into lock step. But the new Internet, the social media Internet, feels to me like it might not have moved revolution along, and may have actually set it back. I think about the way that modern online life has deprived us all of a shared reality. We don't operate from an agreed-upon body of facts, because the profitable product features of social media let each of us build an airtight world of intense, claustrophobic bias. One person's galvanizing experience attending a protest can be instantly shorthanded into meaninglessness by the political filtration system of another person's feed. Our modern information ecosystem turns Black Lives Matter into BLM, the struggle against fascism into Antifa. It is an unquestionably useful organizing tool in the moment. (Protesters in Korea were summoned in part by one opposition leader live-streaming to his 10.7 million subscribers on YouTube from his car.) But over time, would it have drained the struggle against Salazar of its lifeblood, turning 40 years of rebellion against the horrific estado novo into a disarming diminutive, a political shorthand, a handy hashtag?

The rest of our trip was dramatically re-colored by our visit to Aljube. Everyone we encountered above a certain age haunted me. What had they seen? What trauma did they still carry? The domestic and culinary traditions of the city felt to me like side effects of generations of women relegated to second-class status by the conservative, celibate, Catholic Salazar. (One young woman told me that the deepest sexism she endures these days is often from female relatives who lived under the dictatorship.) And the incredible art and design of mid-20th-century Lisbon suddenly felt like a psychological adaptation to tyranny, a way that creative people endure trauma by engaging in decorative art and design, rather than the kind of cathartic creative expression that can get one arrested in a dictatorship. It reminded me of Americans so traumatized by the current political climate that they tell each other (as I have) that they're turning away from politics and toward beauty and creature comforts for the next four years.

I have spent many years interviewing experts in misinformation, totalitarianism, and populism, and to an American who naively assumes, as I have for so long, that democracy is the natural state of a nation, it is shocking to hear about the slow, seeping way that economic dissatisfaction can become a brand of politics that leads directly to deprivation and horror. The events in South Korea, and this trip to Portugal, has me more convinced than ever that the United States is an innocent teenager when it comes to our development as a nation, and our tendency to let the market choose our politics and our economic policy for us is exactly what millions of citizens in Portugal, South Korea, Colombia, Turkey, Uganda, and dozens of other nations would warn us about. And for me the most shocking part was that as a journalist of 25 years, I know so little about their experiences. (If you have any suggestions on books that can help me get up to speed, I’d welcome them.) We enjoy technological conveniences that would have astounded our ancestors, but in the end, even as we are made to feel that we have a heads up about everything, the early haze of totalitarianism can still be blinding as it drifts around us.

If you’re a paid subscriber, comments on this post are open. What more do I need to know about how modern societies have navigated dictatorship? What found light and oxygen in spite of political repression? What qualities died away? And does this worry I have that the technology of the modern attention economy might make democratic revolution harder rather than easier make any sense to you? Thanks, as ever, for reading.