Let’s Reinvent Marriage

Gender inequality, my highly unusual parents, and what the holidays can teach us about how far we have to go.

This is the final Rip Current of 2024, and it’s a departure from my usual dystopia beat. When I began writing these columns, I told myself I’d take occasional leeway to lean into other interests, and one that’s really got me by the throat these days is the reshaping of marriage in the United States and around the world, as we come to grips with the horrors hidden behind traditional unions, and the happiness hidden behind unorthodox ones. I like to believe we’re at the beginning of a very important reinvention of the whole thing.

These two holiday weeks we’re about to spend with our various families are why I’m thinking of this now. This occasion tends to compress all our relationships into a single live-fire exercise, especially for those of us who travel to or host our extended families. Every relationship is tested. Can we still sleep under our parents’ roof? Can we summon the patience to stand, toothbrush in hand, waiting our turn for the bathroom as our younger brother takes his sweet goddamn time? How’s our own relationship to addiction and impulse control, as we sneak a pull of cooking wine in the kitchen or a cigarette on the porch? And all of this, of course, can create a shrapnel cloud of exhaustion and impatience that cuts up the innocent partners and children we’ve dragged along with us. (Whether it’s that we’re so often broken by these tests, or because of a need to keep our plans corked until the New Year, January is known by family attorneys as “divorce month.”) So I want to spend this column talking about marriage, and gender, and upbringing, and my hopes for improving all of it.

I’m lucky enough to be married to an absolutely delightful person. We have two perfect children. I’d do anything to keep this going. And so here’s an important lesson of 16 years together: The news business is relationship poison. The phone buzzing in the middle of the night, dressing in the dark, spontaneous travel, no idea when a trip might end. (And I traveled less often than most.) For the partner suddenly left at home, it’s a special kind of hell.

In my first months working at Al Jazeera, and then at NBC News, I informally polled my male colleagues about their domestic responsibilities, looking for someone who could tell me how to be both a news professional and a father and partner. The straight, married men, with only a handful of exceptions, either had a traditionally unequal arrangement, in which their wife more or less did everything, or were divorced or about to be. A few new fathers were hoping to improve on that record, but the field of possible mentors around this stuff was thin.

The female colleagues I approached, however, somehow seemed to carry the bulk of domestic responsibilities even while acting as a correspondent, a field producer, an anchor. One colleague grilled a doctor about her kid’s upcoming appointment by phone as we drove through a wildfire. Another Fedexed frozen breast milk home from our shoot location. I found their ability to juggle it all absolutely astounding. But asking them to explain how they did it usually resulted in shrugs, or tears, or both.

My own marriage eventually reached the edge as well. My daughters were ten and seven, my wife was working full time, I was constantly traveling, and I remember one evening like so many in which she said to me, turning from her laptop, her eyes welling with exhaustion, “I need help.”

“What kind of help?” I asked, my pulse racing, eager to plug whatever holes she’d found in our battered boat.

“I don’t know,” she said slowly, her voice full of stones. “But this is important. I need you to hear me. I need help.”

I don’t remember how I went on to find Fair Play, the book and card game by Eve Rodsky — like so much of that time my memory of it is a blur — but I remember thinking that if I didn’t bring some sort of solution to the table, we were going to go under.

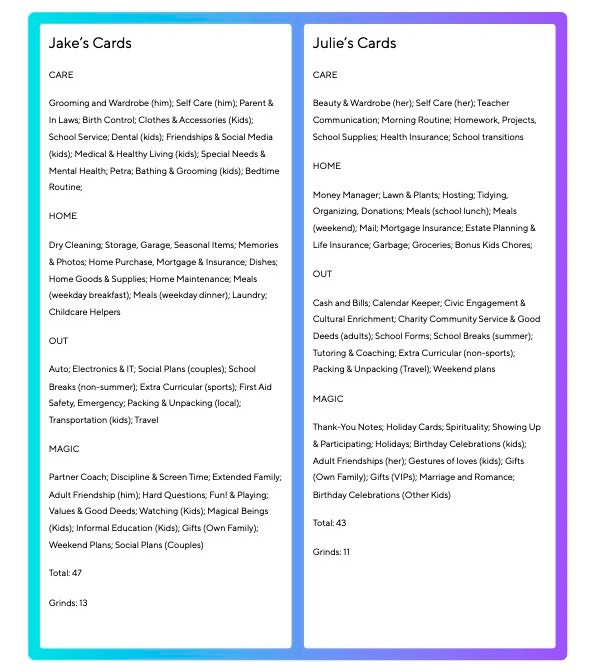

Here’s how I describe Fair Play to the many, many couples I’ve felt compelled to share it with. Rodsky has put together a deck of 100 cards, each of them representing a category of either household or personal responsibility, from logistics like “Weeknight Dinners” or “Home Insurance and Mortgage” to parenting roles like “Difficult Topics” or “Gifts for Others”. Thirty of these are considered “Grinds,” which carry a heavier daily weight, and together they comprise a remarkably complete portrait of the visible and invisible burdens of running a household.

The couple sits and negotiates between them a “minimum standard of care” that applies to each card. (Is the standard for “Laundry” that the towels are scented and folded in thirds and arranged by color? Or is it just that everyone in the house has at least one clean towel available to them?) Then the couple divides the cards between them.

The goal is not, Rodsky points out, to achieve perfect 50-50 mathematical balance. The goal is to achieve psychological balance, such that the cognitive load of the work feels equal. Not every task is of equal weight, and no two people feel the same amount of weight carrying the same task. My wife despises doing the dishes, a task I don’t love but don’t mind. I find it psychologically unaffordable to open and sort the mail, which costs my wife next to nothing.

To hold a card means you are entirely responsible for the concept, planning, and execution of that task. You must hold that responsibility fully, such that no one else has to remind or coach you. In exchange you are also free to meet the minimum standard of care however you wish, without being managed in the process. (As we say it in my house, no back-seat parenting/cleaning/folding.) You may ask for help if you get stuck, but doing so is a pretty egregious violation, reserved for emergencies, so don’t do it. Hold the card. The card is yours.

The rules are in some cases philosophical. For instance: all time is equal. The partner who makes more money than the other doesn’t get to eschew the system. My higher-paying job does not mean my time off is more valuable than my wife’s time off, a nod to the systemic gender pay gap that has remained more or less consistent for the last 20 years.

The cards make room for self-care, from the time each of us needs to attend to personal grooming to the time each of us needs to spend time with friends. Again, all time is equal, whether you’re spending it washing dishes or catching up with a cousin for dinner. It’s just up to you to observe the system so your partner also has time for those opportunities.

No one holds any one card forever. The game requires that you sit together periodically and redistribute the tasks, so neither of you burns out. In my house we’ve achieved sufficient equilibrium that we mostly trade one task for another: I recently took on Friendships and Social Media (Kids) and handed off School Lunches. (Also, hey, just so you know: School Lunches is no problem at first but quickly becomes the grittiest of grinds.)

And ultimately the game is cooperative, not competitive. The object of the game, once you’ve divided the cards and established a minimum standard of care for each, is to earn your partner “Unicorn Time”: a period of extra bandwidth long and capacious enough to accommodate a new hobby, a yoga practice, a part-time degree. Once you’ve earned each other that Unicorn Time, you’re winning the game.

Below is how my wife and I divide the cards right now. (I should point out here that I’m enjoying an enormous amount of free time in my life after NBC News, while my wife continues to work full time, so I’ve absorbed more than I used to.)

We’ve explained Fair Play to perhaps a dozen couples. We once spent an evening with another couple pretending that the four of us were a single household, and divided the cards that way. (It was wonderfully easy to find a willing taker for each card, but there was a single task no one wanted: Thank-You Notes.) I typically get a rapt response from the wife, and a much more muted response from the husband. (I have even had a husband circle back to me to complain that by raising the prospect of using the system I’d made trouble, to which I gently suggested that the trouble was already there, and this was a chance to survive it.) It’s a fascinating catalyst for conversation around gender imbalance, invisible work, and the nature of marriage. But it is also a dark reflection of how poorly all that stuff can go.

While Fair Play was profoundly useful, I at first found the book and its rhetoric deeply irritating.

My reaction had to do with the heteronormative stereotypes that ran through the book. It’s written for straight women trying to salvage their marriages, and I, as husband, was clearly not its intended audience. Ladies, Rodsky was saying, you know how men are. Before you divorce or run your husband over for his uselessness, try my system.

My irritation, of course, was misplaced. The fact that Fair Play found such a vast and clearly desperate audience — it has enjoyed enormous success as a publication, a product, and now a Hulu documentary — is a clear referendum on the state of gender inequality in straight marriages. In her critique of Fair Play, Zawn Villines writes “I have no doubt that Fair Play might work well in a household with a 60/40 split, where there are small differences in labor and the man really does want things to be equal. But this is not the typical household.”

The typical heterosexual household, it turns out, is so far from equity that a single card game can’t help it. Why? Because marriage not only isn’t for everyone, it never was.

Invented as a way of connecting families for political benefit, betrothal has historically offered women nothing more than the possibility of physical and financial security in a brutal world. It wasn’t until the last few centuries that anyone married for love, and even now entering into marriage can of course wind up only being a new form of captivity. As Rebecca Traister puts it in All the Single Ladies, her very thoughtful book about the ways that female independence from marriage has brought about enormous social change, marriage historically “hustled nearly all (non-enslaved) women, regardless of their individual desires, ambitions, circumstances or the quality of available matches, down a single highway toward early heterosexual marriage and motherhood.”

Roughly two million marriages take place in the United States each year. (More than 700,000 of these are same-sex marriages, about which I am not qualified to write, but which I also deeply hope have improved on the track record of straight couples. As of 2018, the majority of same-sex couples living together were married.) Inside the heterosexual unions, families are now on average smaller and more manageable, more women work, and more men are unemployed. Yet men continue to do far less domestic labor than women. (And hey, surprise, men remain more likely than women to report that their marriage is going well, and that household chores are well-divided.)

This imbalance is of course compounded by the fact that this country, with its lack of affordable childcare and unsurvivable minimum wage, doesn’t support families. And most domestic labor is, of course, uncompensated. One estimate puts the annual value of unpaid caregiving by women at $643 billion per year, making their pro-bono contribution to the economy greater than the estimated market value of the semiconductor industry. Meanwhile a pipeline of tradwife influencer and MAGA fantasy has some public figures (including our Vice President-elect) openly suggesting that the single highway of marriage that Traister describes is the most appropriate path for a woman today. And in 2023 the wage gap went the wrong way after being stuck in place for decades, widening for the first time since 2003. No wonder my wife was on the very edge.

Anecdotally, the typical household is pretty ghastly, according to Rodsky. She draws on story after story of endlessly useless men who cannot be entrusted to make and keep an appointment for their children unassisted, men whose wives pack their vacation luggage for them, men who call their wives on a rare getaway overnight to ask where the diapers are kept. (She also, in a cynical but canny move, insists on referring to these as good guys led astray, the sort of tone one takes with a friend who has obviously married the wrong person but will clearly kick you out of her car if you say it out loud.)

I know the men Rodsky describes, although I try to keep them at a distance in my life. And her book helped me understand that while I assumed the spectrum of household division of labor ranged from well-intentioned-but-lacking to perfect, it’s actually more a range from nightmarish to barely acceptable. Fair Play, for all that it lacks, tells us where we are, and how far we have to go.

My naivete about the state of marriage and the division of household labor is something I come by honestly. My mother was a primary-care RN who went on to become an academic and cofounder of a nursing school. She woke up before any of us, commuted long distances, returned just in time to eat dinner together. My father, a freelance writer and historian, was a stay-at-home dad. That was pretty radical in 1974. He saw my sister and me off to school, picked us up afterward, and was the one making the dinner and calling us to set the table as evening fell.

My dad remembers trying to make conversation with the other mothers at the playground when I was a toddler and getting a worried once-over from them in his sandals and his long beard. But he persevered, and as a result I grew up assuming it was normal for one’s father to cook, grocery shop, run bath time, and otherwise function as the domestic center of the household. From an early age I associated fatherhood with the smell of bolognese, with tender counsel, with solace for scraped knees.

My relationship with my mother was close and loving, but it was a more adult kind of relationship, based on intellectual observation and shared humor. She taught me by example and through conversation big, abstract, important lessons about patriarchy and autonomy and feminism. But the intimacy of that early child-parent connection was mostly my Dad’s territory. I remember with shame being asked as we pulled into the garage one evening after a pizza outing who I’d rather have bathtime with, replying “Dad” too quickly, and watching my Mom’s face fall. (I’ve since learned you don’t ask that kind of question of the kid, for everyone’s sake, but my parents were in their twenties at the time.) Happily, my relationship with my Mom hit its stride, but not fully until I was older — a dynamic I’ve heard many people describe in their relationship with their fathers. And my Dad, like so many mothers before him, struggled to disconnect as parents must from his attachment to me during my teenage and college years, and I struggled to disconnect from him. (I’ll be so curious to hear from my sister as to what she recognizes or doesn’t in what I’m writing here. Hi Casey!) It really was a traditional family reversed.

I believed for years that this arrangement was typical, that somewhere out there must be other Dad-at-home families like mine, even though I more or less never encountered one. I remember the strangeness of heading home after school with friends and encountering their mothers offering snacks and a debrief. (Why isn’t Fred’s Mom at work?) I remember accompanying a friend to a musical with his family, and seeing his father’s clear discomfort and unfamiliarity with the chaos of driving children into a city. And I remember time and again explaining to my own visiting friends why my dad was always at our house at 2:45 on a weekday: author, works from home, yes it’s always been this way.

But it wasn’t until I became a father myself that I truly realized how unusual this had all been.

I realized it mostly because my own circumstances didn’t offer me the same role. My father had broken new ground. I was a reversion. My jobs as a magazine editor and then as a television correspondent made me an unreliable domestic partner, prone to unexpected travel. It wore on my wife in painful ways, and it produced in me a resentment it took me years to investigate properly: a disappointment with how rarely I could be around to pick my kids up from school, or otherwise be present in the ways my own father had been. My wife, when she complained about her domestic workload and my absences, received in return complaints from me that she couldn’t see how badly I wanted things to be different.

When I was present, my wife would tell you (I’ve checked with her, it’s true), I carried a pretty equal load, making most dinners, handling doctor’s appointments, cruise-directing the kids’ weekends. And I like to think that in spite of my long absences for work, I have been a good and relatively constant father. But last-minute travel was the true killer in my relationship. I would get calls at all hours to get on a plane right now, often with no clear sense of when I might be returning, and going out the door that way meant I was more or less dumping all the Fair Play cards on my wife, blowing up her chances of Unicorn Time entirely.

For that reason, Fair Play didn’t actually solve our problem. The game clearly didn’t account for a family in which one partner is spontaneously vaporized for days or weeks at a time. It only served to help us understand better that that pattern wasn’t sustainable. If NBC News hadn’t let me go this year, I may very well have had to leave that job anyway, for the good of my family.

It’s only now that I’m no longer responding to breaking news that Fair Play works for us. In this new professional moment I’m in, where I write essays like this from home, our marriage has returned to a much more balanced place, and I’ve become a much more reliable partner. I hope that the lessons of this healthier phase follow me into the next, potentially less healthy one, or at the very least that this phase lasts through these fleeting, irreplaceable years with my kids at home, and doesn’t slide out of balance until after they’ve broken our hearts by growing up.

I’ve encountered more and more men my age or younger who are taking on the role of primary caregiver, as my father did. When I hear them hesitate to admit it, at a dinner party or at school pickup, I leap in as quickly as I can to congratulate them and tell the story of my father, and of how grateful I am to have grown up in his household and under his example. I don’t wish to make myself the center of this analysis, but I do believe that the more children growing up with an ever-present dad cooking dinners and playing bubble-war at bathtime, the better. May we soon enjoy the benefits of millions of fathers who consider it their job to hold cards like Hard Questions, Weekday Meals (Dinner), and Showing Up and Participating. (In fairness my wife holds that last one right now, but I’ll get it back before long.)

Legislation will have to play a role here too, of course. Paid family leave, which compensates caregivers for at least some of their work, has been part of California law since 2004 (although no federal mandate exists) and has been shown to not only improve marriages but, perhaps more importantly, the health and development of children. And national support for early childhood education, which makes it possible for an adult to earn a living while children get the attention and socialization they need, will be crucial here as well.

All of which is to say that Fair Play is, of course, not enough. A revolution in how children learn to be adults, in the struggle to earn a living wage, in the systems that currently abandon parents to market forces that do not want them to raise children well together, is all going to be necessary. But in my own marriage it took Eve Rodsky’s work — and the range of responses I’ve received in discussing it with other drowning couples — to show me that we are as a nation still in a deeply primitive place when it comes to the roles women and men play as partners and parents, one that will require much more than a card game to escape.

In the meantime I hope that you can step back during these next two weeks and watch the family dynamics you see around you — the ones you grew up with, and the ones you’ve carried into your own life as a lover, partner, and parent — with some analytical detachment. Let us all forgive ourselves for the mistakes our parents taught us to make, and begin getting our own relationships ready for the future.

I’ll be back on Monday, January 6th. Happy Holidays.

It is a cliche to thank someone for their frankness after a post like this, but thank you anyway. I can slightly relate, in that the pandemic provided a salutary balance-reset drill in my own marriage: I had just quit Google thinking I would spend 2020 traveling and singing in choirs (haha, says the universe, ha. Ha.) and Catharine’s job went into sudden high gear as network traffic 10x’ed worldwide, so I was stay at home dad, housekeeper, and de facto homeschool teacher for the year instead. We were ludicrously privileged to be able to work it out that way— our friends who had two full-time jobs and kids at home were sooooo much more stressed.

A friend of mine named Cathy Reisenwitz has, from a *very* different personal perspective, written some insightful stuff on her ‘stack (cathyreisenwitz.substack.com) about how whether marriage is a good deal has come to depend much more on your economic class, and how that exacerbates inequality and creates an increasing number of angry single men. That seems like an underappreciated driver of a whole lot of social trends, from declining fertility to increasing support for right-wing authoritarians among young men.