Efficiency Will Take, Not Give

What will efficiency provide? More days off? Greater safety? Think again. This chaotic political and economic moment gives the powerful what they want, and creates the opportunity for disaster.

Early in my career, a colleague of mine, a veteran magazine editor, found himself with a surprising amount of free time. He’d been liberated from a couple of monthly responsibilities, and at a workplace where most of us were grinding until all hours of the night, he became a free spirit, wandering from desk to desk, offering upbeat advice and ideas. I remember him as a typically downcast figure, but now he was full of light, and in the office kitchen one morning I asked him in a typical coffee-making moment how things were going.

“I’ve been head-down for so long I haven’t been able to think more than a couple of days into the future,” he said, clearly startled by his good fortune. “Suddenly I’m able to call up writers and sources and start cooking up longer-term projects. It’s wonderful!”

Those of you who’ve worked in any sort of corporate setting know what happened next. He was canned a week or so later. The free time he’d been given was a pre-layoff reassigning of responsibilities. I never encountered him again.

I think about him whenever I hear the promise that technology is going to hand us enormous amounts of free time, that the efficiency made possible by something like an AI assistant or AI co-author will usher in a better work-life balance, granting us free hours for art, a bit of sculpture, a new language.

The predictions about AI’s ability to make our lives better by making our professional achievements more efficient are based on the assumption that corporations bestow efficiency on working people as some sort of compensation, rather than using it to burden them further. You see this in reports that do the simple math and conclude that AI could bestow a four-day work week on 28% of a national workforce. But AI is causing the bosses to expect more from their employees, according to several studies, including this one from Upwork.

77% of employees report that these tools have added to their workload. Employees report spending more time reviewing or moderating AI-generated content (39%), investing more time learning how to use these tools (23%), and being asked to do more work as a direct result of AI (21%).

Because of course that’s how the market works. It’s not a garden in which free time is protected and allowed to grow. It’s a vacuum that sucks in all free time around it. And under the current economic and political circumstances, when executives are reasserting control over workers and a record number of billionaires are suddenly running the government, that vacuum is growing stronger and stronger.

Some nerdy reading has taught me a name for this dynamic: the Jevons Paradox. It’s a well-known term for the economists among you, but I only learned about it last year.

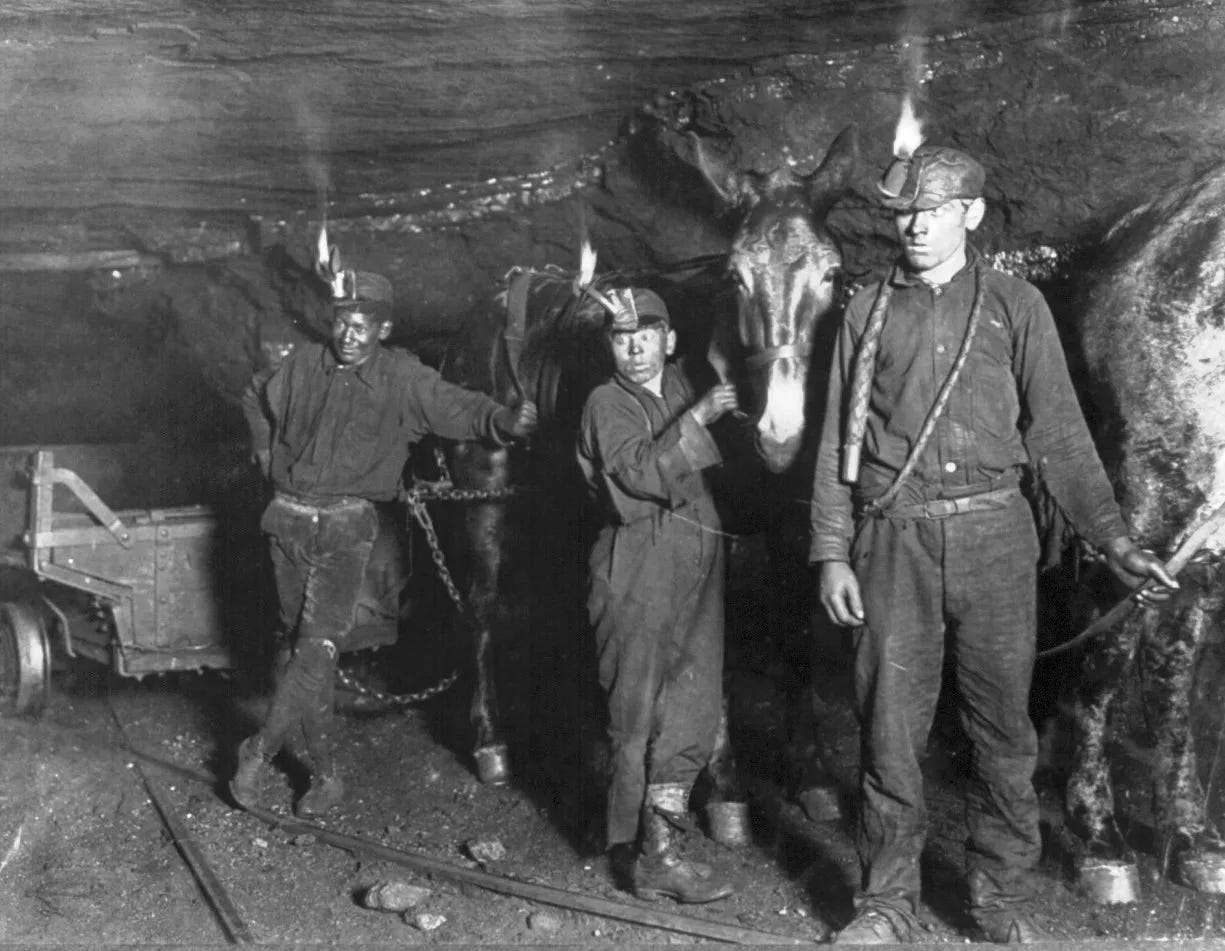

Between 1776 and the 1880s, engineers in England refined the design of steam engines such that they conserved heat and as a result used less coal. But that didn’t slow down the consumption of coal — it only seemed to result in burning more of it.

The English economist William Stanley Jevons thought that the British Empire’s reliance on this finite fuel source could eventually be its undoing, and explored the problem in his 1885 book The Coal Question, which carried the no-fucking-around subtitle An Inquiry Concerning the Progress of the Nation, and the Probable Exhaustion of Our Coal-mines, and the no-fucking-around thesis that when the British Empire used coal more efficiently, it was less likely to conserve it, and would eventually run out, and therefore fall from power.

The Jevons Paradox turns out to haunt other places where technology offers an improvement in efficiency, only to see market forces erase that improvement by demanding even more of the resource. Scholars have directly linked increases in efficiency to increases in consumption of everything from electricity to water.

I’ve seen people bend over backwards to use the Jevons Paradox to explain the effects of drone strikes, or the future of software development. But I like to keep it simple. The efficient use of time in your work as an administrative assistant, mortgage broker, or customer-service agent is no different than the efficient use of coal, energy, water. When this technology makes our use of time more efficient, the market will take more of our time.

Here, of course, I could go on and on about how the current foundational models like ChatGPT, Gemini, or Llama may only be distractions that do not lead to the artificial general intelligence we’ve been promised, or about how the climate cannot afford the energy demands of the data centers needed to power these systems, or that each day our requests for questionable images of sexy, scary grandmas [don’t click please] are boiling away lakefuls of precious water as coolant. But let’s put that aside for the moment, you’ll get plenty about all of that from me in other posts.

In a nation where half of us can't put together $500 in an emergency, when time is saved, its value falls, and the demands on our time increase. At the very moment we should in theory have to work less, we're being forced to work more. Ask any store clerk working at a retailer like Target or Wal-Mart. Over the course of more than 30 years, their wages have remained more or less stagnant, while their on-the-job responsibilities have grown more than ten times.

Hear that? That's Jevons thrashing around in his coffin.

(In fact, I believe that if we’re going to give anyone productivity tools that would have Jevons whacking his head into the wall, it should be people who aren’t immediately beholden to market forces, and who are committed to doing redeeming things with them, and that’s scientists. But I’ll get into that in a later piece.)

I’m thinking about all of this because of recent moves by OpenAI, which on Thursday hosted a Washington, DC, event for regulators and lawmakers called “Building to Win: AI Economics,” where the company pushed its policy suggestions and announced a new deal to provide its technology to the national labs for research into cybersecurity, foundational science, and nuclear security. And earlier this week the company announced ChatGPT Gov, a new AI for government agencies that, according to OpenAI, will “enhance service delivery to the American people through AI and…foster public trust in this critical technology.” ChatGPT Gov will supposedly allow more efficient internal processes, reduce time spent on routine tasks, and summarize and interpret written communications. At the event Thursday, an OpenAI employee demonstrated how a government employee could ask ChatGPT Gov for a five-week action plan, incorporate feedback, draft a legal and compliance memo about it, and translate it into other languages, according to CNBC.

It’s all part of a new cozy relationship between OpenAI and the Trump administration. In fact, “cozy” is the word two democratic senators used in a letter to Altman on January 17th (one he went on to post on X), accusing him and the CEOs of Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft and Meta of trying to win influence by spending a million dollars of his own money on the president’s inaugural fund, pointing out that “you have a clear and direct interest in obtaining favors from the incoming administration.” (He and the other CEOs are instructed to respond to the letter today, January 31st.) Altman’s appearance last week to announce a Trump-endorsed, SoftBank-funded plan to build vast data infrastructure for the company, nicknamed Stargate (I go on and on about the name here), and now this AI-for-government idea, not to mention OpenAI’s burgeoning defense contracts, don’t exactly rebut the senators’ accusation.

In theory the push for efficiency should and could result in better processes for Americans. Other countries have created technologically advanced civic systems that we’d kill for.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Rip Current by Jacob Ward to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.